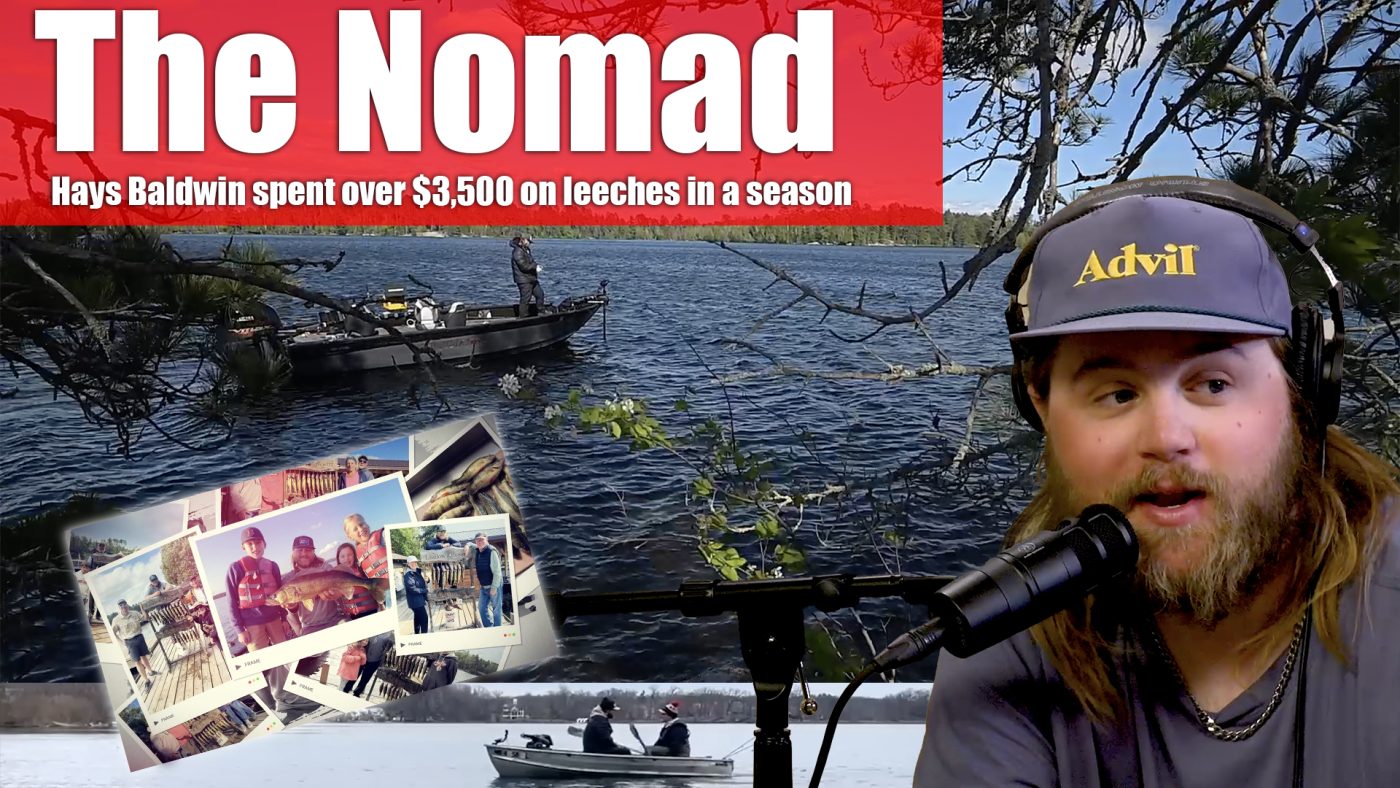

A Life Consumed by Fishing

Hays Baldwin is the definition of a fishing bum—someone who’s truly consumed by the sport.

If he could fish 365 days a year, he would. In fact, he spends around 300 days annually on the water, chasing a variety of species across Minnesota and beyond.

While he’s a dedicated fishing guide on Lake Vermilion during the open water season, his pursuit of fish doesn’t stop there. Whether it’s panfish in spring, walleyes in summer, or largemouth bass in fall, Hays is always on the move, often living out of the back of his truck to stay close to the best bites.

Chasing Bites Year-Round

Hays’ season begins on hardwater, splitting his time between local metro lakes like Minnetonka and northern destinations like Lake of the Woods and Red Lake. As the ice thaws, he transitions into spring guiding on Minnetonka for crappies and then kicks off the open water season with the walleye opener on Gull Lake, a tradition he’s kept for over a decade. By early summer, he relocates to Lake Vermilion, guiding for walleyes straight through to October. Once he’s had his fill of walleye, it’s bass fishing time—an important seasonal pivot that helps him stay engaged and sharp across multiple species.

Why Lake Vermilion?

Hayes was drawn to Vermilion for its size, complexity, and habitat density. “Everywhere you look is a good-looking spot,” he explains. The lake’s biomass is astounding—catching 20 fish off a spot only to return the next morning and find 40 more is not uncommon. Vermilion’s slot limit (protecting fish from 20–26 inches) helps ensure a high-quality fishery that delivers both quantity and trophy potential. Hays recalls his first year on the lake, landing five walleyes over 28 inches in a single outing, with the biggest stretching to 29.25 inches. That kind of day is rare almost anywhere outside of the Lake of the Woods.

Seasonal Movement and Habitat Focus

Hays has dialed in a seasonal game plan on Vermilion. In May and June, he focuses on the west side of the lake, where shallow water, rich weed beds, and solid structure concentrate fish. The east side, in contrast, offers less weed growth but holds its own in terms of productivity. He’s a big believer in fishing weeds for walleyes, a tactic that’s become more common as technology has revealed just how often walleyes use vegetation for cover and feeding.

Drawing from his early days fishing Brainerd-area lakes, Hays learned that weeds are a reliable and underutilized pattern, especially in spring. While rocks and gravel flats still play a role, many fish now actively relate to vegetation, and understanding this shift has made Hayes more versatile as an angler and guide.

Slip Bobbers and Live Bait: Simplicity That Works

When guiding novice anglers, Hayes leans on proven, simple presentations. “Slip bobbers and leeches are a go-to,” he says. Not only do they catch walleyes, but they also produce bass, bluegills, and other species—keeping clients engaged. For more experienced guests, he may also turn to jig and minnow or crawler combos, but for weed-related walleye fishing, the slip bobber remains king.

Over the years, the live bait bill has added up—Hays once spent over $3,500 on leeches in a season before switching to nightcrawlers. Last season alone, he purchased nine flats of crawlers (about 4,500 worms) to meet client demand.

What Clients Want: The Fish Fry Metric

Though some trips are catch-and-release, especially for bass, the majority of Hays’ walleye clients are there for one reason: the fish fry. Roughly 85% of the time, clients are looking to bring home eaters, targeting fish between 12 and 18 inches. Due to the slot limit, big fish over 20 inches must be released, which often leads to interesting client reactions. Hayes recalls days where they’d catch 15 walleyes—all too big to keep—and clients were disappointed despite the incredible quality of the catch.

To address this, Hays shifts zones as the season progresses. In July and August, he moves toward the middle and eastern parts of the lake. These less-pressured areas offer plenty of eater-sized walleyes and fewer boats. Plus, the eastern end holds excellent smallmouth bass fishing thanks to its rock structure, adding variety and opportunities for catch-and-release sport fishing.

By the Numbers: A Thousand Walleyes and Counting

Hays keeps detailed journals of his guiding seasons, tracking fish kept and trips run. In his first year on Vermilion, he and his clients kept about 1,000 walleyes. That number rose to 1,200 last year across 160+ guide trips—averaging 8–9 keeper walleyes per outing. While the numbers may seem high, Hayes is quick to point out that modern anglers are far more conservation-minded than in decades past.

He draws a sharp contrast to the old days, citing stories from the early 20th century when guides would pile muskies into wheelbarrows and “kill everything.” Hays is both respectful of the past and mindful of sustainability—acknowledging the need for responsible harvest and better practices while continuing a legacy of passionate, dedicated guiding.

A Nod to Guiding History

As much as Hays loves fishing today, he’s also a student of the sport’s history. He references legendary Brainerd-area guide Harry Van Dorn, recalling stories from a book of classic Minnesota fishing tales that detail Van Dorn’s work out of the now-defunct McMaster’s Resort. These anecdotes, along with modern-day journaling, form a bridge between old-school guiding traditions and today’s high-tech, conservation-minded approach.

From the Old School to High-Tech: Evolving Ethics and Approaches in Fishing

Stories from Minnesota’s guiding history can be awe-inspiring—and staggering. One such tale from 1954 details legendary guide Harry Van Dorn putting up numbers that boggle the modern mind. That summer on Gull Lake alone, he reportedly harvested 2,300 walleyes. A particularly memorable day involved guiding three women from Iowa to Sandy Beach Resort where they hauled in a stringer of ten fish weighing a jaw-dropping 97 pounds, including multiple 12-pounders.

Those days of unregulated abundance are long gone, and with good reason. Historical photographs of trains or docks lined with hundreds of dead fish paint a vivid picture of how dramatically attitudes and regulations have changed. Conservation efforts, modern regulations, and angler ethics have come a long way, especially when compared to those freewheeling harvest eras.

Were Anglers of the Past Better?

While it’s tempting to romanticize the past, it’s also worth examining the skill required to be successful back then. As Hays points out, those old-timers didn’t have sonar, GPS, or digital maps. “They were lining up with a pine tree on shore,” he says. Fishing back then demanded intense observation, intuition, and patience—skills that modern electronics have significantly supplemented, if not replaced.

Hays freely admits he’s adapted to the times, relying heavily on technology like forward-facing sonar and LiveScope. It’s become so integral to his process that fishing without it now feels unnatural. “It’s like my umbilical cord,” he jokes. But even with all this tech, he knows how to fish without it—and proved that two years ago in a local walleye league, where he and his partner won without using forward-facing sonar, beating teams that had every tool at their disposal.

The Game-Changer: Forward-Facing Sonar

There’s no question LiveScope and other forward-facing sonar systems have revolutionized fishing. For experienced anglers, Hays believes it might double their catch rates. But for less-skilled anglers, the boost is far more dramatic—potentially multiplying their effectiveness fivefold or more.

That’s where ethical and management concerns begin to surface. As more people adopt this technology, and as catch rates soar, the cumulative pressure on fish populations increases. Especially vulnerable are species like panfish during the ice fishing season. “You used to burn a whole tank of auger gas drilling holes. Now, with LiveScope, you might drill one and find a whole school,” Hays explains. While it makes the sport more accessible and efficient, it also raises red flags for overharvest—particularly on smaller lakes.

Ice Fishing and the Technology Divide

The difference is most pronounced on the ice. Panfish, which often school tightly in winter, are now far easier to locate and catch. As a result, Minnesota has started implementing five-fish panfish limits on some heavily pressured lakes near areas like Otter Tail and Big Pine. Hays applauds the move, noting that guides and anglers alike are becoming more aware of the long-term impacts of heavy harvest.

In contrast, he sees less relevance for walleyes under the ice. “They never stop moving,” he explains, making them harder to pin down even with advanced electronics. Still, the process of finding fish, regardless of species, is faster and more efficient than ever.

Managing Big Waters Responsibly

On expansive bodies of water like Lake Vermilion, the situation is more forgiving. With 50,000 acres and a healthy natural reproduction system supported by localized stocking efforts, Hays feels confident that the lake can handle a reasonable level of harvest. He notes that the Minnesota DNR stocks fry—around five million per side—every two years from native egg takes out of Pike Bay.

Even so, Hays believes stocking programs will become increasingly critical in the coming years. As pressure from more effective anglers continues to mount, natural reproduction alone may not be enough to maintain quality fisheries.

The Ethics of Future Tech

As technology continues to evolve, so do the ethical questions. What happens when sonar not only shows a fish’s presence but also identifies the species? Hayes draws the line there. “At that point, is it even fishing anymore?” he wonders.

He’s not against technology—far from it. He’s embraced it fully. But he also believes in drawing boundaries, particularly when new tools threaten to eliminate the challenge and mystery that make fishing what it is. “I’m pretty proficient with it,” he says, referencing the ability to find and catch walleyes in rocky, shallow zones he never would have considered before LiveScope.

A Call for Nuance

Ultimately, Hayes argues for a balanced approach. The conversation around fishing technology doesn’t have to be an all-or-nothing proposition. There are contexts where advanced electronics enhance enjoyment, education, and success without causing harm. And then there are situations—particularly in small, pressured systems—where restraint and regulation are essential.

“There are areas where we should probably say, ‘Whoa, hey…’” Hayes notes. And as he and other guides continue to refine their approaches, they remain at the front lines of a sport—and a resource—that’s changing faster than ever before.

Generational Shifts, Tech Adoption, and the New Age of Ice Fishing

A Call for Balanced Perspectives

As the conversation around technology in fishing deepens, Hays emphasizes the importance of open-mindedness. He points out that his generation often embraces new tech without fully considering its implications, while older anglers may resist it out of unfamiliarity. But instead of falling into these stereotypes, Hays urges a middle-ground approach: “Sit back and listen to both sides.” That mindset has shaped his view not just on electronics, but on broader questions of conservation, fair use, and what it means to be a responsible angler in the 21st century.

The Learning Curve and the Changing Experience

For young anglers today, the learning curve has dramatically shortened. Hayes grew up fishing competitively as a teenager, learning through trial, error, and experience. But now, 16-year-olds can jump into tournament-ready boats loaded with electronics and gear, having immediate access to powerful tools that took decades for older generations to acquire.

However, Hays is quick to point out that technology alone doesn’t make a great angler. “Just because you have forward-facing sonar doesn’t mean you’re catching fish,” he says. There’s still skill, time, and intuition involved. But he admits that sometimes, the immersive focus on screens and sonar can detract from the natural experience. “I’ll look up and be like, ‘Whoa, there’s an eagle!’” he laughs. The landscape, the wild, the moments that make fishing soulful—those can get lost when your eyes are glued to the graph.

The Rise of Real-Time Networks

What’s also changing the game is the speed of information. Hays belongs to a hyper-connected group of hardcore anglers who are constantly trading intel. They’re in touch with buddies in South Dakota, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and all over Minnesota—constantly scouting, analyzing, and reacting to hot bites.

This network allows them to be nimble, mobile, and opportunistic. They’ll jump on early ice bites, hit new lakes before the crowds, and get the most out of each season by leaning on collective knowledge. For Hayes, the chase is just as exciting as the catch—pushing out onto thin ice with safety gear in search of untouched walleye schools is part of the thrill.

Ice Fishing with Forward-Facing Sonar: A New Era

One of the most dramatic shifts has come in the world of ice fishing, especially for panfish. Hayes shares vivid accounts of early ice outings, including an adventure on Round Lake where he and his buddy Bill caught six- and seven-pound walleyes in just inches of ice. Safety is always a concern, but being among the first on the ice—well before others arrive—is part of what makes these moments so electric.

And when they’re on the ice, the impact of forward-facing sonar is undeniable. Hays reflects on how Red Lake’s crappie population is thriving—but perhaps only for another year or two before increased pressure and exposure take their toll. Despite limits on species like perch being reduced on lakes like Mille Lacs, crappie regulations on Red remain unchanged, even though the fish are large and increasingly vulnerable to harvest.

Mille Lacs Perch and the Power of LiveScope

Hays shares a detailed example of how technology has changed the game on Mille Lacs, particularly in a video series with Sobe. On the north end of the lake, he and his crew were able to identify pods of jumbo perch on the mud flats using forward-facing sonar. Instead of drilling hundreds of holes like in the past, they could locate blips on the screen, drill strategically, and drop baits directly on fish.

The system became highly refined: one angler ran the LiveScope, another drilled, and a third followed up with rods and flashers. It allowed three people to fish out of a single hole and maximize catch rates. Yet, it wasn’t entirely effortless. “We still went through batteries on augers,” Hayes notes, explaining how perch often shift just a few feet out of range once drilling starts—meaning precision is still crucial.

Crappie Patterns Reimagined

Crappies, in particular, have become far more accessible due to modern sonar. In the past, anglers would blindly drill and swing their flashers in hope. But forward-facing sonar reveals a new truth: the fish were often there all along—just shifting out of transducer range at the sound of drilling. Now, with improved optics, these hidden schools are revealed, providing both a new understanding and fresh opportunities.

Adapting to Exposure: The Push for New Water

As technology and communication increase exposure, anglers like Hayes are thinking ahead. “Things are going to get exposed quicker than ever before,” he says. That’s why exploring new water—often aided by DNR tools, satellite imagery, and mapping software—is becoming essential. He encourages others to break away from the habit of revisiting the same lakes and spots repeatedly. The goal: discover, preserve, and reduce pressure on popular systems.

While there’s undeniable excitement in revisiting productive bites like Mille Lacs perch or Red Lake crappies, Hayes is working toward a more balanced approach. “Maybe let a few bites rest,” he says. It’s all part of a broader vision—staying ahead of the curve while being thoughtful about the impact on the fisheries that make all of this possible.

Tech Meets Tackle: Exploring New Water, Tools, and Techniques

The Thrill of the Hunt: Finding New Water

For passionate anglers like Hayes, nothing matches the excitement of discovering new bites on fresh water. It’s what drives him—scrolling endlessly through lake surveys, staring at depth maps, and piecing together fish patterns. “It’s what gets my blood going,” he says. Tools like OnX and the Minnesota DNR LakeFinder have become essential to this pursuit. Whether checking land ownership for public access or using survey data to identify promising species populations, these digital resources open doors to lakes previously overlooked.

The convenience is unmatched: find a lake, push a button, and your phone routes you there via Apple CarPlay. But with that access comes responsibility. Hayes stresses the importance of mindful harvest and selective fishing. The ease of access and improved efficiency brought on by forward-facing sonar and digital mapping has increased pressure on fisheries. That, he argues, makes it all the more vital to consider the long-term health of these resources.

Disappearing Crappies and the Mystery of White vs. Black

Hays has spent plenty of time deep in the lake data rabbit hole—sometimes flipping through 90+ pages of survey results in a single night. One trend that puzzles him: the apparent disappearance of large white crappies from many of the metro lakes he grew up fishing. “They just vanished,” he says, and lake surveys back him up: from dozens netted in the early 2010s to just a couple in recent years.

Interestingly, some lakes have seen white crappies reappear years later. Hybrid crappies—crosses between white and black—may play a role in growing trophy-sized fish, with many anglers noting that the true giants often come from waters with both species present. Still, black crappies tend to be more stable, consistently regenerating, while bluegill populations—once depleted—often struggle to recover.

The Obsession with High-End Bass Gear

When Hays isn’t dissecting walleye structure or chasing crappies, he’s diving headfirst into the bass world—another facet of his all-species, all-season approach. He’s constantly collecting new baits, especially Japanese Domestic Market (JDM) lures, many of which are designed with forward-facing sonar in mind.

Through his friend Aaron Teal and The Bass Galaxy podcast, Hayes has been introduced to some of the latest innovations in finesse bass fishing. These baits are often unconventional in shape, material, and even name—some bordering on comical or risqué. But functionally, they’re incredibly effective, especially when paired with real-time sonar that allows anglers to see how fish react to different presentations.

“I want to get really good with it for smallmouth,” Hays says, adding that Lake Vermilion, with its diverse structure and deep, clear waters, is the perfect proving ground.

The Irony of Simplicity: How LiveScope Changed the Game

Despite all the high-tech tackle and flashy packaging, the rise of forward-facing sonar has created an unexpected twist: a return to simple, proven presentations. Whether it’s a jig and a crawler or a slip bobber and leech, Hayes notes that many of the most effective baits are classics. “You drop it right on their head, and they’ll bite it,” he says. Many of the once-dominant techniques—like blade trolling, spinner rigs, or pulling crankbaits—have taken a back seat to vertical precision targeting.

This isn’t just preference—it’s efficiency. When you can see the fish in real time and put a bait right in front of them, the need for elaborate rigs or trolling passes fades. That said, Hayes still incorporates trolling into his strategy, especially for covering water in big, deep areas.

“Mowing the Grass”: Trolling in a Tech-Driven World

While Hays doesn’t consider himself a hardcore troller, he’s found great success using leadcore line, snap weights, and crankbaits—particularly on Vermilion. In fact, he’s seen boats using downriggers up there with impressive results, something more commonly associated with the Great Lakes.

Trolling has allowed him to learn the nuances of lure depth, lead lengths, and water color impact. “I call it mowing the grass,” he says, describing how he trolls mud flats and deep sand areas in wide, systematic passes, using LiveScope to adjust course and stay on fish.

Even in July, during the bright midday hours, crankbaits still produce on Vermilion, likely due to the lake’s darker water. That wouldn’t necessarily work on clearer lakes near home. It’s another reminder that every tactic has a time and place—and knowing when to apply each is part of what separates seasoned anglers from the pack.

As Hayes refines his approach, blending old-school simplicity with cutting-edge tools, one thing remains constant: his relentless curiosity. Whether it’s finding a new lake, trying a new bait, or unlocking a new pattern, the pursuit never ends—and that’s exactly how he likes it.

The Changing Role of Trolling and the Evolution of Competitive Fishing

The Rise—and Fade—of Traditional Trolling

While trolling used to dominate competitive walleye fishing—especially throughout the 2000s and early 2010s—its role in the high-stakes world of professional angling has shifted dramatically. Hayes reflects on how techniques like leadcore, downriggers, and snap weights were once the gold standard, particularly on massive bodies of water like Lake Erie. Now, many of those once-essential skills have been overshadowed by a new era of precision casting powered by forward-facing sonar.

That’s not to say trolling is obsolete. Far from it. Hayes still sees immense value in mastering the technical aspects—adjusting snap weights, understanding lead line lengths, choosing the right crankbait, and more. “It’s super cool,” he says. “There’s a lot of nuance and detail to it if you want to really learn the craft.” But in the competitive space, particularly at the National Walleye Tour level, it’s now a screen-driven show.

On big, open water—especially during summer—casting with forward-facing sonar is winning tournaments. Hayes cites recent catch-and-release walleye events on Lake of the Woods where five-fish stringers topped 50 pounds. “That’s insanity,” he says. And it’s being done not by trolling deep basins with leadcore, but by casting at specific fish suspended in open water—an incredible shift.

Forward-Facing Sonar: Not All Positive, Not All Negative

Hayes continues to emphasize that he holds a neutral stance on LiveScope and similar technologies. He uses them, he appreciates their power, and he acknowledges their drawbacks. He’s careful not to sound like a critic, but instead positions himself as an observer: someone who fishes over 300 days a year, sees what’s happening in real time, and is honest about the impacts.

He notes that on many smaller lakes—excluding giants like Vermilion or Lake of the Woods—fishing is objectively getting harder. The “dumb” fish are gone, he says. Pressured, educated fish are becoming increasingly difficult to catch with previously successful techniques like jigging raps or even bobber fishing. “I truly believe less fish are going to get caught,” he explains. “Not more.”

That has consequences not just for seasoned guides like Hayes, but for everyday anglers as well. The technology arms race is pushing up costs, and those without the latest gear may find themselves left behind—or simply frustrated. “They’re getting priced out,” Hayes says bluntly. “At what point do you draw the line?”

From Golfer to Guide: A Life Lived Outdoors

Though he now spends most of his time on the water, Hayes has a background in golf, too. He played in high school, and his grandfather was a club pro at the historic Lafayette Club on Lake Minnetonka. “I used to throw a buzzbait off the driving range and catch bass before golfing,” he laughs.

And even now, he sneaks in rounds when he can. One of his best performances came last year with a 75 at The Quarry—despite barely playing for months. Around Vermilion, with courses like Giants Ridge and Fortune Bay nearby, it’s not uncommon for his clients to play golf in the afternoon after catching a morning limit of walleyes.

The YouTube Generation: Filming the Grind

Hayes is part of the new wave of anglers who live—and film—their fishing adventures for online audiences. Collaborating with creators like Sobe, Bill, and others, he’s helping document modern fishing culture one 20-minute video at a time. But while the polished end product might seem effortless, the reality is anything but.

“There’s a lot more that goes into it than people see,” Hayes says. Countless outings yield little to no usable footage. Skunks happen. Cameras die. Fish don’t cooperate. But the grind of filming is part of the appeal. “That’s what keeps me coming back,” he admits. “It’s the challenge.”

To make it work, you’ve got to love fishing as a lifestyle—not just a hobby. Between GoPros, phones, editing gear, and the constant push to learn something new, the YouTube grind mirrors the passion and persistence that defines modern angling.

Embracing the Process, Learning from Failure

Failure is part of the journey. And in fishing, failure is often the best teacher. “When you get your ass handed to you,” Hayes says, “you learn to appreciate the process. You ask, where did I screw up? How can I fix it?”

That drive to adapt, evolve, and improve is what keeps anglers like Hayes on the water day after day. Whether it’s refining trolling tactics, experimenting with Japanese finesse baits, or diving into the data behind fish population trends, it all stems from one thing: a love for the process. And in a rapidly changing world of fishing, that mindset might be the most valuable tool of all.

Walleye Nights and Final Thoughts: Why Lake Vermilion Belongs on Your Bucket List

A Living Laboratory: Learning Every Day on Vermilion

For Hayes, every hour on Lake Vermilion brings new information, new patterns, and new surprises. With nearly 50,000 acres of diverse structure, habitat, and species, it’s a constantly evolving puzzle. From Head of the Lakes Bay to Armstrong Bay, he’s found that patterns repeat themselves across the system—offering both consistency and complexity. “There’s just so much going on,” he says. “It’s total overload, in the best way.”

What makes Vermilion special is its Canadian Shield feel—rugged, remote, and full of opportunity—yet it’s all within Minnesota. You don’t need a passport to experience wilderness fishing here. Whether you’re exploring back bays, casting to structure you spotted with your eyes, or dialing in a pattern that works across the lake, Vermilion gives anglers the ability to fish their own way—and catch fish doing it.

An Open Invitation to Explore

Three seasons into guiding on Vermilion, Hayes remains just as excited as he was on day one. “I knew nothing when I showed up,” he says. “And now, I realize how much I still have to learn.” That’s the beauty of Vermilion—it’s deep enough, vast enough, and dynamic enough to offer a lifetime of discovery. Whether you book a trip with Hayes or head up to explore on your own, his message is clear: just go.

The Night Shift: Targeting Walleyes After Dark

For those willing to put in the extra hours, night fishing on Vermilion and other Minnesota lakes can be incredibly productive—especially in spring and fall. While many anglers think darker water means less potential after sunset, Hayes assures that the night bite can be lights out, particularly when water clarity improves in cooler months.

His preferred setup is simple: flatline trolling with spinning rods, 10-pound braid, and a snap swivel. Stick baits like Shadow Raps, original Rapala floaters, and other shallow-diving crankbaits get the call. In early spring and late fall, slow trolling at 1.2 to 1.6 mph across shallow flats can be deadly. “It’s all about that slow roll,” he says.

As summer progresses, Hayes speeds things up and adjusts baits accordingly, but the principles remain the same—subtle, steady, and close to structure.

Casting After Dark: The Magic of the Rip’n Rap

When it comes to casting, Hayes is all-in on the Rapala Rip’n Rap, especially the size 6 in natural colors like blue chrome. But instead of the typical aggressive ripping cadence, he fishes it slow—almost dragging it across sand flats, letting it lift just a few inches off the bottom before letting it fall.

“You’re just pulling it,” he explains. “They eat it on the drop.” In colder water, this subtle approach is incredibly effective. While the bait’s name suggests violent jerks, the key to success is restraint—letting the bait work near the bottom and triggering bites from neutral or negative walleyes.

In fall, the bite transitions back to larger stick baits. Bigger baits like 13s or BX Swimmers work well, as fall walleyes key in on larger meals. Hayes laughs at how even small fish will crush these giant offerings, proving that size isn’t always a deterrent.

Fishing, Filming, and Full-Time Passion

As the conversation wraps up, Hayes reflects on what drives him: the process. Whether he’s experimenting with new techniques, exploring untouched water, filming with buddies like Sobe, or just soaking in another Vermilion sunrise, he’s all in.

“There’s a lot more that goes into this than people think,” he says. Filming is a grind, editing takes time, and many trips don’t yield usable footage. But the reward is in the pursuit—figuring things out, adapting, and sharing that passion with others. “It can’t be just a hobby,” he says. “It’s got to be a lifestyle.”

Hayes embodies the modern multi-species angler: highly skilled, tech-savvy, conservation-minded, and completely dedicated. His perspective—shaped by hundreds of days on the water each year—offers valuable insight into where the sport of fishing is headed and what it means to balance innovation with responsibility.

From slipping a jig through spring weeds to pulling big baits on fall nights, from exploring crappie cycles to breaking down trolling systems, Hays has seen—and done—a little bit of everything. But for all the gear, gadgets, and new methods, one thing stays the same: it’s about being out there, learning, adjusting, and enjoying the process.

So if you’re looking for your next destination, Hayes has a simple pitch: “Come fish with me. Or go fish it yourself. Just get up to Vermilion—it’s freaking awesome.”